Ever wondered about the life of one of history’s most infamous rulers? King Xerxes I, known for his massive invasion of Greece in 480 BC, was a complex and often misunderstood figure.

This article presents an enlightening look into the life and reign of this notable Persian king. Dive in to unravel twelve fascinating facts that offer deeper insights into his royal journey.

Key Takeaways

- Xerxes I was the fourth King of Kings in the Achaemenid Empire, born to King Darius I and Queen Atossa.

- His mother, Atossa, played a crucial role in his ascension to the throne and continued advising him throughout his reign.

- Xerxes attempted to complete his father’s Greek campaigns but failed to conquer Greece.

Born to King Darius I the Great: The Early Life of Xerxes

Xerxes, the fourth King of Kings in the Achaemenid Empire, was born to King Darius I and Queen Atossa around 519 BC. Seen as a royal gift from birth, his path to greatness seemed predetermined.

Xerxes grew up during a significant period in Persian history as his father expanded the empire through successful military campaigns.

Despite being second-born, he decided to succeed his father on the throne after demonstrating impressive leadership qualities at an early age. His mother, Queen Atossa who was daughter of Emperor Cyrus the Great influenced this decision by heavily pressing for her son’s rise over Darius’ firstborn Artabazan by his previous wife.

As part of Persian tradition for royalty, young Xerxes received education from eunuchs appointed by King Darius I himself. His childhood years were spent learning about governance and military strategy which prepared him for future roles.

King Xerxes’ Accession To the Throne was Due To His Mother

Atossa, King Xerxes’ mother, wielded enormous influence over the Persian royal court. She was a former queen to Cyrus the Great and Darius I, making her position within the kingdom beyond dispute.

After Darius died in 486 BC, Atossa had a pivotal role in supporting her son Xerxes claim to the throne.

She maneuvered through palace politics smartly, ensuring her son won favor among key nobles and military leaders. Her power extended beyond the throne room and stretched across Persia’s vast empire.

Without Atossa’s steady hand guiding his ascension, King Xerxes might have lost his right to rule.

Xerxes assumed kingship under his mother’s guidance on an auspicious day that astrologers prescribed as favorable for this grand event. The transition of power was smooth primarily due to Atossa’s planning and popularity among influential Persians who respected her wisdom.

She continued advising him throughout his reign which led King Xerxes becoming one of Persia’s most notable rulers in history.

Xerxes was Educated and Brought up by Eunuchs

Eunuchs, often entrusted with significant roles in Persian courts, had a hand molding the future king. They had been tasked with educating young Xerxes I. Under their watchful eyes and guidance, Xerxes acquired vast knowledge of statecraft, history, artistry, and military strategy.

The intimate involvement of eunuchs in his upbringing also influenced his perception of ruling. Their singular devotion to service gave him insights into fairness and justice while instilling the firmness necessary for a King of Kings.

This unique education set the stage for both his ambitious pursuits and spectacular failures later as ruler over the Achaemenid Empire.

Khashaayaar Is The Correct Pronunciation Of King Xerxes’s

Name

Khashaayaar is how King Xerxes’ name should be pronounced. This pronunciation reflects the ancient Persian language he would have spoken during his rule. The correct way to say his name emphasizes the “kh” sound at the beginning and ends with a soft “r” sound.

So, when talking about this famous Persian king, it’s important to use the proper pronunciation of Khashaayaar rather than other variations that may be commonly heard or used today.

Xerxes was A Great Womanizer

King Xerxes was known for his womanizing habits. He had a reputation for being involved with numerous women during his rule. Xerxes I’s womanizing behavior often led to scandal and controversy within the empire.

Despite his other accomplishments and military campaigns, Xerxes I’s personal life and relationships are often discussed as a significant aspect of his reign. His womanizing tendencies were just one part of the complex persona that shaped his legacy in history books.

During Xerxes I’s time as king, he was focused on expanding the empire and indulging in romantic affairs with various women. These relationships brought pleasure and pain to those involved, creating intrigue amongst court members and causing tensions within the palace walls.

It is evident that Xerxes I’s womanizing ways shaped how others perceived him during this era of ancient Persia.

Overall, it is clear that Xerxes I’s reputation as a great womanizer has left an indelible mark on history. While other aspects of his rule may be worth discussing, it cannot be denied that his personal life and relationships have become an integral part of understanding who he was as a ruler and individual.

Xerxes Attempted to Finish Darius’ Greek Campaigns

Xerxes I, the fourth King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, sought to complete his father’s Greek campaigns. His invasion of Greece in 480 BC was a key part of this mission. Xerxes I amassed an army of more than one million soldiers for this endeavor.

Despite his efforts, however, he ultimately failed to conquer Greece and achieve his goal. This setback marked a significant turning point in the interactions between Persia and Greece, shaping the history of the Achaemenid Empire.

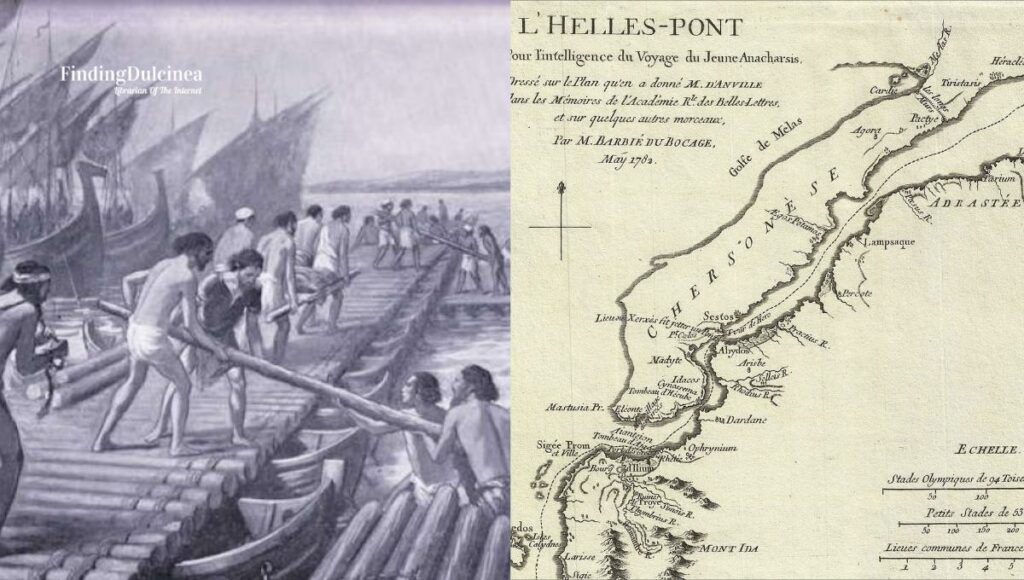

He tried to Cross the Hellespont

Xerxes made a bold attempt to cross the Hellespont. This narrow strait separated Europe from Asia and proved to be quite challenging.

With his massive army numbering over a million soldiers, Xerxes I ordered the construction of two bridges to facilitate his crossing. However, Mother Nature had other plans. A storm destroyed one of the bridges, leading Xerxes I to lash out at the sea by having it whipped as punishment for its disobedience.

Despite this setback, he eventually crossed and continued his ambitious invasion of Greece in 480 BC.

Xerxes I’s endeavor to conquer Greece showcases both his determination and command over vast resources at his disposal. It was a pivotal moment in history that shaped his reign and influenced future interactions between Persia and Greece for generations to come.

Xerxes recognized the right to be Happy

Xerxes I made a significant contribution to his empire by recognizing the right to be happy. During his rule, he understood the importance of happiness among his subjects.

Xerxes I believed that a happy population would lead to a prosperous and stable kingdom. As a result, he implemented policies to improve his people’s well-being and contentment.

This recognition highlights Xerxes I’s progressive mindset and his desire for harmony within his empire.

Under Xerxes I’s leadership, efforts were made to ensure that individuals had access to opportunities that brought them joy and fulfillment. He encouraged cultural activities, such as music, art, and festivals, which allowed people to celebrate their traditions and express themselves creatively.

Additionally, Xerxes I promoted religious tolerance and respected diverse beliefs within his empire. This enabled people from different backgrounds to practice their faiths without fear or oppression freely.

Xerxes I recognized that happiness was not only essential for individuals but also vital for maintaining social cohesion in his empire. By acknowledging this right, he fostered an environment where people could thrive both personally and collectively.

His actions reflect a ruler who prioritized power and the well-being of those he governed—a rare trait in ancient times.

Xerxes Crushed Revolts In Babylon And Egypt

Xerxes I proved his power by crushing revolts in Babylon and Egypt. During his rule from 486 BC to 465 BC, he faced rebellions in these critical regions of his vast empire.

With decisive action, Xerxes swiftly suppressed the uprisings and maintained control over these territories. His military prowess and strategic leadership allowed him to quell internal unrest and ensure stability within his empire.

This feat showcased Xerxes’ determination to maintain order and solidify Persian dominance over these vital parts of his kingdom.

He Nearly Bankrupted Persia To Complete His Father’s Construction Work

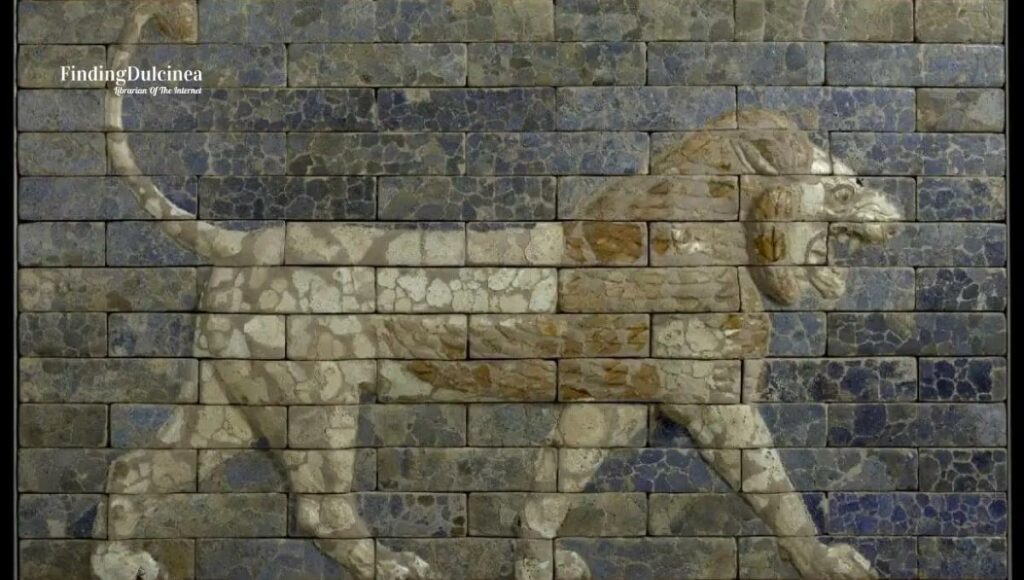

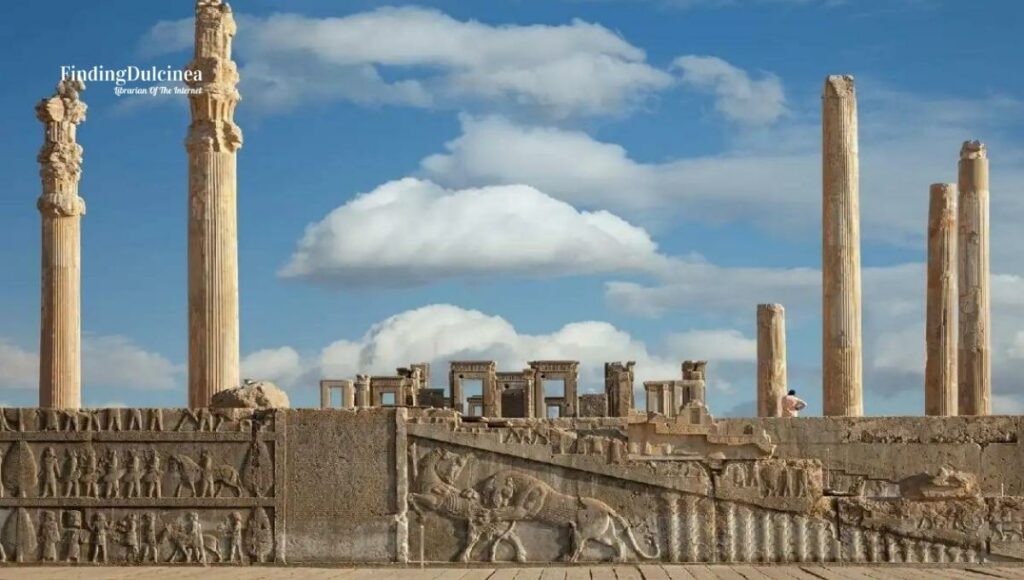

Xerxes I’s ambitious construction projects nearly bankrupted Persia. In an effort to complete the work started by his father, King Darius I, Xerxes poured vast amounts of wealth into building massive palaces and other architectural structures.

The expenses required for these grand endeavors drained the Persian empire’s coffers and put a strain on its resources. Despite the financial challenges, Xerxes was determined to leave a lasting legacy through his extravagant constructions.

His commitment to completing his father’s work showcases his dedication to preserving and solidifying the power of the Achaemenid Empire.

His Own Advisor assassinated King Xerxes

King Xerxes met a tragic end when he was assassinated by his own advisor. This shocking event took place in 465 BC, putting an abrupt end to Xerxes’ rule.

Despite his accomplishments and grand ambitions, his trusted advisor turned against him.

Throughout his reign, Xerxes had faced numerous challenges and made enemies along the way. However, someone from within his inner circle ultimately plotted against him and carried out this treacherous act.

The murder of King Xerxes by his advisor remains a haunting mystery that has puzzled historians for centuries.

With this assassination, Persia lost a powerful leader who had significantly impacted its history and relations with other nations. The sudden demise of King Xerxes changed the course of the Achaemenid Empire’s future and marked the end of an era filled with grand ambitions and mighty conquests.

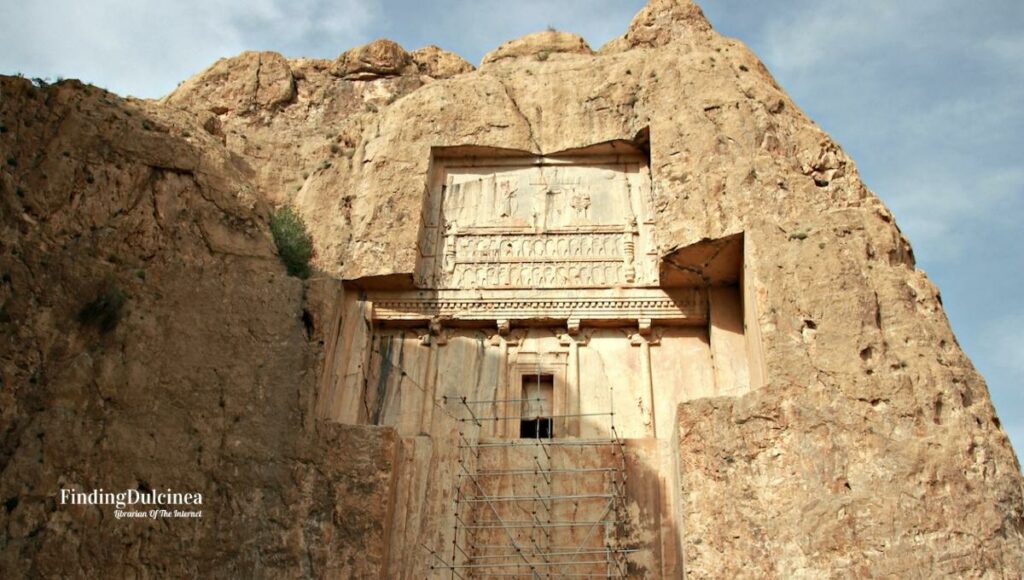

He is buried near Shiraz Iran

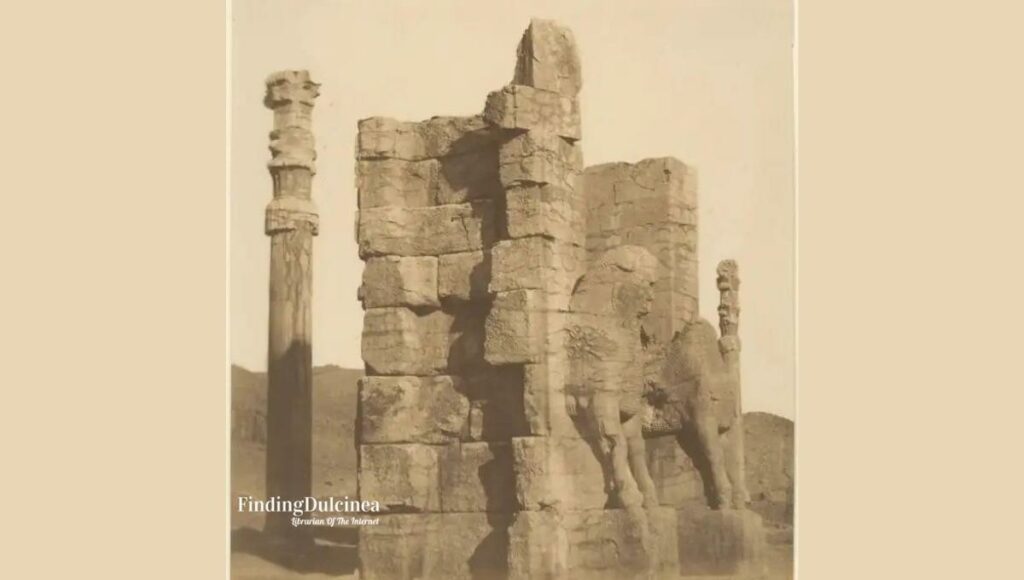

Xerxes is laid to rest near Shiraz Iran. After his assassination in 465 BC, Xerxes I was buried in a grand tomb befitting his status as a powerful ruler.

The location near Shiraz holds historical significance as it showcases the final resting place of an emperor who played a significant role in Persian and Greek interactions. Today, visitors can explore this burial site and witness the legacy left behind by Xerxes I’s reign.

FAQs

Who was King Xerxes I in history?

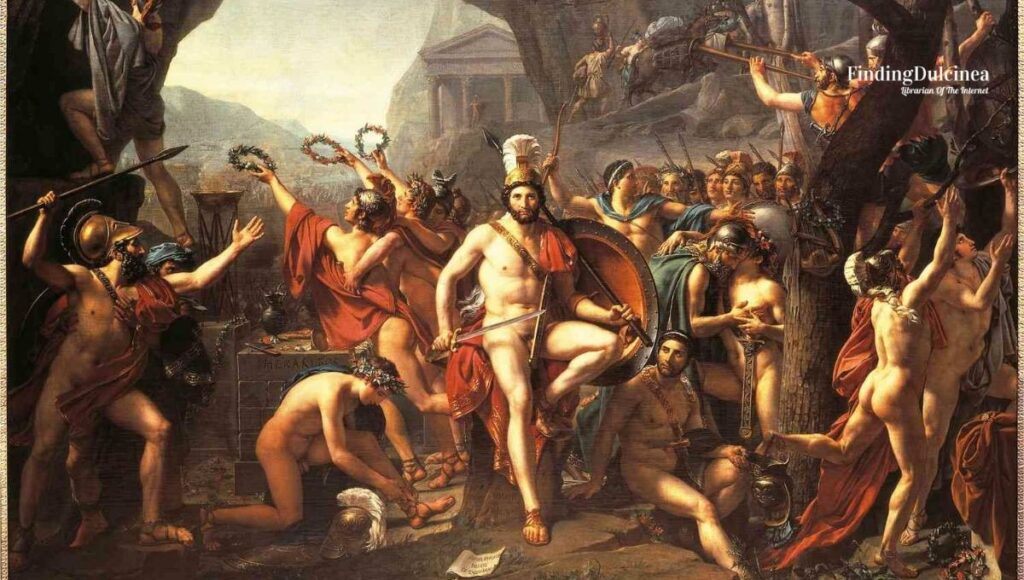

King Xerxes I was a prominent ruler of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 486 BCE to 465 BCE. He was the son of Darius I the Great and succeeded him after his death. Xerxes is perhaps best known for his ambitious but ultimately unsuccessful military campaigns against Greece, particularly the battles of Thermopylae, Artemisium, and Salamis.

What is King Xerxes I best known for in history?

King Xerxes I of Persia is best known for his role in the Greco-Persian Wars, particularly the invasion of Greece in 480 BCE.

How long did King Xerxes I rule?

King Xerxes I ruled the Achaemenid Empire from 486 BCE to 465 BCE, a total of 21 years. He succeeded his father, Darius I, and was eventually succeeded by his son, Artaxerxes I.

Colleen joined findingDulcinea in April 2007. Her 15 years of copywriting experience includes writing for a start-up robotics company, an online gourmet foods importer, an engineering firm and a law firm. She also spent four years as a Direct Online Marketing Manager for John Wiley & Sons, producing and managing all e-mail and online promotions for seven product lines. In 2005, she taught English to children and adults in Mexico, and practiced her Spanglish in Guatemala and Cuba. Colleen has a B.A. in Languages and Literature from Bard College. To learn more about Colleen read her blog, Cha Cha Chow or follow Colleen on Twitter.